Move Fast and Break Deliberately

Speed is good, aimlessness is not. How to code fast while mind the dashboard lights.

In 2009 Facebook’s rallying cry—“Move fast and break things”—echoed through the halls of every startup. It celebrates speed over caution, which is important in a startup, but does it apply to developed companies that have aging code bases?

For those companies, (and for startups for that matter) the future technical debt of moving fast creates major problems.

We see this in Facebook itself as in 2014 the company walked back the mantra, switching to “Move fast with stable infrastructure.” Not as catchy. Not really the thing that can be shouted on the rooftops of silicon valley justifying poor development in the name of “proving out an idea”. So… was it adopted by venture capital folks? Of course not— investors, to this day, are still quoting the original. For them, and for the larger companies that want to mimic the environment of startups, I propose a new mantra: “Move fast and break things… deliberately.” Breaking deliberately means deciding what to break—and, just as crucially, what must stay intact.

The analogy I’ll be using in this article will compare tech debt to car maintenance. I was skeptical it would work at first, but I like of like it.

TL;DR

Mantra upgrade: Move fast and break deliberately—speed is good, aimlessness is not.

Tech‑debt flavors: deliberate, accidental, bit‑rot, documentation, testing, architectural.

Rule of one: tolerate exactly one debt bucket when moving fast and document the deliberate debt you’re accepting.

Don’t accept more than one type of technical debt at a time

Bottom line: plan the mess you’ll clean up later, or the mess will plan your roadmap for you.

What Is Technical Debt?

(As always skip this section if you’re familiar with the general breakdown of technical debts)

Technical debt is the future cost of today’s shortcuts—refactoring time, bug fixes, lost velocity.

I believe technical debt comes in six flavors, and they’re each handy for a product manager to be familiar with as they are asking their development team to rapidly deploy things.

Deliberate Debt – chosen shortcuts for speed with a cleanup plan.

Accidental Debt – low‑quality code from inexperience or unclear requirements.

Bit‑Rot (Outdated) Debt – aging frameworks, libraries, or stacks that lag behind standards.

Documentation Debt – missing or stale docs that slow onboarding and maintenance.

Testing Debt – sparse automation that raises bug risk and manual effort.

Architectural Debt – structural compromises that strangle scalability and performance.

How do these debt types map to cars?

• Deliberate Debt – “I can drive a few thousand more miles before an oil change.”

Accidental Debt – A buddy promises they can paint your car a new color using oil paint. Occasionally, (hopefully not often) you drive through the wall of a grocery store and start a fire that needs some help from others (fire fighters or SRE’s).

Bit‑Rot Debt – after years on the road, newer cars boast better mileage and features.

Documentation Debt – not registering your car on time, misplacing service records, or forgetting tire size at purchase time.

Testing Debt – skipping regular tune‑ups and safety checks.

Architectural Debt – fitting diesel parts in a gas engine: everything goes brrr… broken.

Which Debt Is Worth Accepting?

Rule of thumb: never incur architectural debt. Architectural debt is a sign of moving too fast and breaking too many things and is likely the key reason Facebook changed it’s mantra to the 2014 mantra of, “Move fast and code with good infrastructure”. Architectural debt can force heavy rewrites and will thwart all future efforts of moving fast in the future. Move fast… but don’t put nos in your engine when you have a 1992 Honda Civic.

Accidental debt happens, and will happen more if you go fast, but it there’s not much we can do about it, so ignore it in the calculus.

Otherwise, choose one other debt bucket to tolerate; guard the rest ruthlessly. This is important. It will feel like you can accept more than one of the debt types while you are coding, but doing so will stymie your ability to move fast in the future.

Option 1 – Documentation Debt

Skip docs only if code is future‑proofed and well‑tested.

Choose this when…

• Your domain logic is stable and unlikely to pivot next quarter.

• You have rock‑solid unit/integration tests catching regressions.

• The team is small and tribal knowledge can spread over coffee.

• You can schedule “doc‑catch‑up day” before the next big hire.

Red flag: Multiple time‑zones or imminent onboarding? Don’t trust on tribal memory—write the docs.

Option 2 – Bit‑Rot Debt

Ship disposable experiments quickly; document them and keep tests green so you can revert safely.

Choose this when…

• You’re A/B‑testing UI tweaks or feature toggles with a short half‑life.

• Market fit is hazy and learning speed beats code longevity.

• Your rollback plan is tested and one‑click.

• The experiment lives behind a feature flag you can yank at will.

Red flag: Core domain or revenue‑critical path? Build it to last, otherwise you’ll be moving too fast and will be too highly depended on in order to go back and fix the… choices your team made.

Option 3 – Testing Debt

If tests are costly now, invest in rock‑solid design and thorough documentation. Buy time today; plan automated coverage for tomorrow.

Choose this when…

• Setting up CI/CD or mocks would delay a funding‑critical demo.

• The codebase is modular and manual QA can cover edges for a sprint or two.

• You have veteran engineers who write defensively and log obsessively.

• You’ve budgeted a “testing sprint” on the roadmap (and leadership signed off).

Red flag: Rapid‑fire releases or multiple parallel feature branches? Skipping tests will bite—invest early.

The Gamble of Stacking Debts

So what if you throw caution to the wind and accept two—or (you daredevil) three—debt types at once?

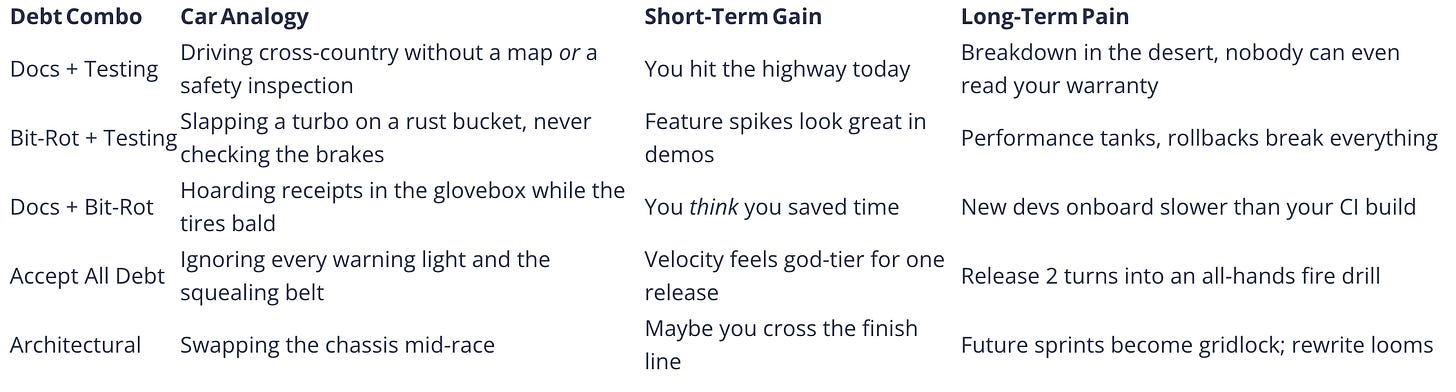

A table for those of you considering this… novel approach.

Your debt stacks multiply. If you accept more than one of these technical debts in a project, cognitive load rises, bugs hide and won’t be found via testing, and every roadmap estimate secretly inflates. Stack too many and your “move fast” turns into drive through a lake and wish you had a boat.

My Garage is Already Messy

The goal of this isn’t to remove tech debt entirely, but it is to document it and ensure that it falls into the “Deliberate” tech debt scenario. If you are about to touch a section of code that already has say, poor documentation, then as you move through it you will already have to take time to understand it… why not add that documentation as you go? Fix, or iterate, on the major sections of tech debt as you perform spikes for the next section of code where you want to move fast. You won’t be able to break things deliberately if you don’t know the full scope of the code you’re about to break.

Documenting (from a technical perspective) the deliberate debt you want to incur during the move fast period is key. That way when you hop back in you know exactly where the deficiencies are and you can continue down the path of that single deficiency (if you absolutely have to) or you can perform micro improvements on that dataset as you figure out the next deliberate thing you want to ignore.

It’s important to note that when you move fast, you do make sacrifices. The ideal situation is that you can handle all aspects of these debts as you go, via “boom” and “bust” periods of development. Think of it like the seasons and code quickly in the sprint, and slowly in the winter.

That way your repos engine won’t shut down right as the warranty expires.